non-fiction

C’era una volta… la passione infinita: breve storia del cellulare

Mapping

Prime navigazioni in rete: introduzione alle reti informatiche

The Shaping of Hypertextual Narrative

Protected: Augmented Learning – The development of a learning environment in augmented reality

Gli ipertesti e la comunicazione multimediale

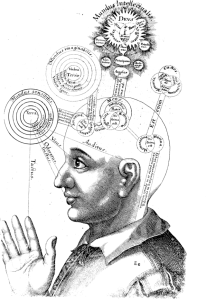

Is there a mind in this mind?

Augmented learning

fiction

Mapping

|

|

|

Territory: the field of action or thought or domain or province of something. Map: a graphical representation or charting of the whole or part of the earth's surface, the heavens or one of the heavenly bodies; anything which resembles a map in appearance or function. |

Setting. There is a scenography of talking about language. I organize it, manipulate it, cut out a portion of space in which I shall mime the act of writing. This is then acted out as a monologue.[1] The scenography is the mapping of the verbal territory I will move in. By writing, I create the space for my words, I give shape to the borders of that/this space; I install a territory. The motion in the territory is slow, circular, rhizomatic, fast, contradictory, tangential, redundant, grouped in constellations, stopped, annihilated by short-circuits. Back and forward. Back again. With repetitions. With interruptions. Forward again. I hope that the impasses I will find myself trapped in will become the openings for my escapes. |

||

Mazes. Running away from his hunter, Hsi P'eng thinks about the labyrinth created by his great-grandfather Ts'ui Pên. He thinks: |

||

Under the trees of England I meditated on this lost and perhaps mythical labyrinth. I imagined it untouched and perfect on the secret summit of some mountain; I imagined it drowned under rise paddies or beneath the sea; I imagined it infinite, made not only of eight-sided pavilions and of twisting paths but also of rivers, provinces and kingdoms. ... I thought of a maze of mazes, of a sinuous ever growing maze which would take in both past and future and would somehow involve the stars.[2] |

||

Is discourse on language through language like Ts'ui Pên's maze of words? So vast as to include the stars? If this maze is infinite (or, more simply, just indefinite), then my questions (my walking through the maze?) will never take me to the borders of the maze, or let me entirely grasp its shapes. |

||

Lost. I acknowledge the infinity of the maze; I accept my inability at finding an exit. What else can I do, then, but keep going through the paths of the maze, trying to understand the working of some of its parts, some of its structures [structures, yes, but not essences or universals; structures: temporary centers, dynamic things, attractors of meaning(s), other mazes -- worlds, maybe], some of the connections among paths? Should I look for some directions that will take me somewhere, even when this 'somewhere' is inexorably inside the maze? |

||

Where is somewhere? |

||

Questions. Are you looking for foundations? For essences? You, reader, might ask. Yes, I answer. No, I answer. I look for coordinates. References. A (one-of-the-possible) territory(ies) and its(their) map(s). |

||

Ideology. It creates subjects. Determines their consciousness as social beings. Their behaviors. Shapes their unconscious. Creates a world. Gives this world the consistency of reality. Gives this reality the power of inevitability. Of inalterability. Of necessity. Of uniqueness. Creates the World. Ideology masks its own masking itself as ideological system. That's how it stays alive. Reproduces itself. Proliferates. We, the Subjects, are the beloved and loving children of Reality. [3] How can ideology create The World? How does it hide its practices of creation? If ideology is "the necessary condition of action within the social formation," then how can I choose an ideology whose practice is (also) the unmasking of its own practice of hiding? (Can I have an ideology that is meta-ideology of itself?) |

||

My (temporary) ideology.

A language is a system; a set of elements and a set of relations existing between these elements. Relations are codes, correlational devices embodying cultural conventions. The elements are signs, pieces in the game of communication.[4] In the game of creation. In the game of deception, falsification, masking. In discourse. |

||

Signification.

"Man lives with his objects chiefly [...] as language presents them to him," says Ernst Cassirer through the voice of Wilhelm van Humboldt. "Each language draws a magic circle round the people to which it belongs, a circle from which there is no escape save by stepping out of it into another."[5] |

||

Saussure. Let's (re)read the well-known passage by Saussure: |

||

Take a Knight (in the game of chess). By itself is it an element of the game? Certainly not, for by its material makeup ‑‑outside its square and the other conditions of the game‑‑ it means nothing to the player; it becomes a real concrete element only when endowed with value and wedded to it.[7] |

||

A sign, either verbal or non‑verbal, is like the knight in the game of chess. It has a value only upon the framework within which we can see (define? understand? use?) it. I change the framework, and that sign loses its value, disappears. Or acquires a new value according to the new rules of the new system of signification that I have chosen (have I?) to use. (How much would you pay for that beautiful knight that you saw through the window of an antique shop? Did you feel pain when I hit you, straight into your eye, with the knight you bought and now keep on your fireplace? I am sorry; I was trying to communicate...). |

||

Peirce. "A sign," writes C. Peirce, "is something which stands for somebody in the place of something else under certain circumstances and capabilities."[8] If I take for good this definition (can I?, should I?), knowing the impossibility of a total (fixed, univocal) signification, I (like to) accept the idea that the signified of a sign is a dynamic item, a "cultural unit"[9] whose conditions of existence and whose temporary stability precisely depend on certain circumstances and capabilities, that is, on the way(s) that sign is defined and used within a particular semantic space and at a specified time. The semantic space is defined/chosen by a certain (more or less identifiable (Identifiable?)) 'community' which shares the same (The Same?) culture (culture=system of values, beliefs, truths, games, rituals, etc.) and agrees (to a more or less extent) about the role(s) that one sign has within one or more linguistic systems. The time is the (more or less identifiable) moment/age in which that community uses that sign with the (or one possible) intention of communicating.[10] |

||

Evolution.

We do not possess documentable records of the forms of communication employed by early hominid species. We cannot really account for the evolution of a non-linguistic signaling-system into an aural articulated language enabling a possible flexible segmentation of the 'perceivable continuum' into discrete unities.[11] So, agnosticism on the origin of language might seem a reasonable position.[12] |

||

Origins. The story goes like this:[13] the first humans lived in groups; as other animals did: mammals, for example. In their communication, they used behavioral signals evolved for group protection: tactile, non-vocal, visual, postural signals. Climate changes (cold, darkness) forced the development of these non-syntactical signals into mostly auditory signals, incidental calls that, little by little, become intentional calls. So, it was time for the coming of modifiers articulating the forms of intentional calls. And then, a further transformation occurred: the birth of nouns, for animals and things, the new power for 'seeing' animals and things, for manipulating them. By naming a thing, you can 'represent' the named thing in its absence, you can recreate an hallucination of that thing within a mental space. And if the beings in a group could name an animal, and could name a thing, why couldn't they name themselves as members of the group? The age of proper names was coming. And with it, the age for the birth of the self, too. |

||

What is left.

When there is no more room for what is left, what is left has to remain untold. Or simply sketched, so much to resemble a parody. What is left lies on the exploration of further paths: the connections between Jaynes's new-born hallucinating I and the birth of the Subject; and then: mirrors, the mirror stage, the separation between the self and the other, between the other and the world, the strengthening of self-awareness, and then the finer, constant division of the continuum, the better articulation of acoustic signals into clearly distinguishable (cultural) units. |

||

Language and (mis)understandings.

A square living in a bidimensional world would seem a line to the lines living in a mono-dimensional world. A cube living in a three-dimensional world would seem a square to the squares living in flat-land. The cubes speak cube-language: the squares speak square-language: the lines speak line-language. A cube decides to visit flat-land. A square decides to visit mono-land. The cube wants to talk to the squares. The square wants to talk to the lines. During these conversations, the squares think they understand the cube, the lines think they understand the square. |

||

Language and landings. Read this story: |

||

A flying saucer creature named Zog arrived on Earth to explain how wars could be prevented and how cancer could be cured. He brought the information from Margo, a planet where the natives conversed by means of farts and tap dancing. |

||

I think this: I imagine Zog landing next to my house and trying to talk to me. I think that I would never be able to (under)stand him. And how could I like Zog, anyway? How could an intelligent being talk to me by means of farts? Is that a language? And even if it is so: if it is true that we possess and are possessed by the language we use, if The World is a product of the language we possess, then, what kind of world does Zog live in? Fart-land? How could he hope to communicate with me? Of course I would brain him with a golfclub! Or with a gun, maybe (my language - The Language - allows me to create a gun. And to use it, too). |

||

Language and humans. Remember this passage: |

||

"Is a cat a man, Huck?" |

||

My question: is Zog an intelligent being? Yes? WELL, den! Dad blame it, why doan' he TALK like an intelligent being? You answer me DAT! |

||

Ideology. Am I being ideological? No, I'm not. It's so evident that I'm not! |

||

NOTES 1. Cf. Roland, Barthes. A Lover's Discourse. Fragments. New York: Hill and Wang, 1978, 19857: 37. => 2. Jorge L.Borges. Ficciones. New York & Toronto: A. Knopf, 1993: 71. => 3. On the formation of the subject in ideology, see Catherine, Belsey. Critical Practice. London & New York: Routledge, 1980, 19926: 56-84. See also the section on "Ideology" in Easthope & McGowan (eds.). A Critical and Cultural Theory reader. Toronto & Buffalo: Univ. of Toronto Press, 1992, and, in particular: Luis, Althusser, excerpt from "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses," 1970: 50-58. For a semiological account on the ways ideology manipulates its semantic world by emphasizing some properties (belonging to a set of statements) and, at the same time, by hiding some other contradictory properties (belonging to the same statements) that would endanger the stability and the linearity of the ideological discourse, see Umberto, Eco. A Theory of Semiotics. Indiana University Press, 1975. It. trans. Trattato di semiotica generale. Milano: Bompiani, 1978: 359-371. => 4. For an articulated (historical) definition of system, sign, code cf. Winfried, Nöth. Handbook of Semiotics. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1990; in part. see chapter II, III.=> 5. Quoted in Ernst, Cassirer. Language and Myth. London: Dover Publication INC., 1953: 9. => 6. I'm not very original, of course. I know. But, after all, this is the let motive of the majority of our almost-new philosophies of language and our more recent theories of literary and cultural criticism. => 7. Ferdinand, Saussure. Course in General Linguistics. London: Fontana: 67. => 8. Peirce. "Collected Papers," 2.228, quoted in Eco. A Theory of Semiotics. Cit.: 26. => 9. Eco. A Theory of, cit.: 98. => 10. This notion of sign, it should be noted, does not refer to the stable/static concept of sign within a static system of signification as defined in/by the structuralist practice. Cf. Robert, Young. "Post‑Structuralism: An Introduction." Untying the Text. Young, R. (ed.). Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981: 1‑28. It seems to me that such a way of intending the sign as a dynamic item should allow (or, at least, should get close enough to) a conception of meaning (never graspable in its (metaphysical) totality) accounting for what Julia Kristeva calls the heterogeneity of signifying process. Cf. Julia, Kristeva, excerpt from "The System and the Speaking Subject," (1973). A Critical and Cultural... A. Easthope & K. McGowan (eds.). Cit.: 77-80. => 11. See Paul, Churchland. "On the Problem of Truth and the Immensity of Conceptual Space." Realism and Representation. Levine, G. (ed.). Madison: The Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 1993: 44-69; also see the discussion on the segmentation of the 'perceivable continuum' into distinct and discreet physical units in Eco, A Theory of Semiotics. Cit.. Although the authors do not give an account for the historical development of the verbal language, they let us see how the 'unshaped matter' of the 'perceivable continuum' could be 'perceived' (by the brain, thought as a biological device capable of transforming patterns of stimulations into sets of populations of neurons, each of which would 'represent'[stand for] an identified portion of the continuum) and divided into units within at least one system [the expressive system] which accounts for their positions and oppositions [their differences]. => 12. Cf. John, Lyons. Semantics, vol.I. London-New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1977: 85-94. On the segmentation of the continuum see also Eco, Trattato di Semiotica Generale. Cit.: 232-238. => 13. Here, I'm using the 'reconstruction' suggested by Julian, Jaynes. The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990. => 14. Here the path becomes much larger and slippery. Just a few labels: Lacan, Althusser, Kristeva. To these, showing some lights on some ideological processes of (mis)construction of the subject and the world, I would also like to add here another name: Nelson Goodman, with his Ways of Worldmaking, (strangely enough, quoted only once in a book like Realism and Representation, dealing with the making of reality. After all, isn't "Reality" what we generate by '(re)creating' worlds?). => 15. Kurt, Vonnegut. Breakfast of Champions. New York: Dell Publishing, 1971: 58. => |

||

Leave a Reply