non-fiction

Io, l’autore e il narratore

Prime navigazioni in rete: introduzione alle reti informatiche

Augmented Learning: An E-Learning Environment In Augmented Reality For Older Adults

Total Theatre and the Transformative Potential of Augmented Total Theatre In Arts, Culture, and Education

The Shaping of Hypertextual Narrative

Analysis Of An E-Learning Augmented Environment: A Semiotic Approach To Augmented Reality Applications

Nota critica: Walter J. Ong – Oralità e scrittura. Le tecnologie della parola

Towards a definition of multimediality

fiction

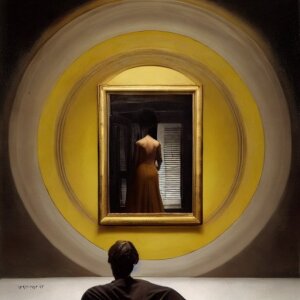

Is there a body in this body?

| University of Florida - 1995 |

|

|

Profanation and death of the body

The age of electronic communication -- it is said -- is the age of the negation of the body. In an interesting and irritating essay, Paul Virilio becomes spokesman for the redeemers of the physical reality of the body. He writes: If, after all, nihilism is just a way to live at a distance from our sensible experiences, it arises from the growing of the techniques for illusion: on the one hand, the 'motor' illusion of the means of transportation, on the other hand the illusion of an emotion provoked by all the most recent audiovisual means of communication.(1)

Fast means of transportation and the instantaneous communications have zeroed the extension of the world, so that individuals have been forced to become their own territories of exploration and experimentation. Inward, feeding with illusions, accumulating the distance from their sensible body, toward the annihilation of their physicality, their carnality and their biology. The contemporary technological operator, coated with electromagnetic omnipotence, plunged in the insubstantial reality of cyberspace or virtual reality, can forget the 'here' and 'now' and go somewhere else without really going anywhere.  Where is the old, safe reality we got accustomed to? Is this really going to be the age of the death of the body? Is the body facing the same death God and Art and Meaning have quite often had to cope with? Through the electronic disintegration, are we becoming just the simulacra of our own real selves? Of course we should analyze and unmask the seductive power of the techno-culture; but can we really state, as Kroker and Virilio seem to do, that the electronic highways, together with the virtual culture, are just sophisticated systems in charge for the dissolution of our body and of the experience of reality?(3) The Frankenstein syndrome and Olimpia's disease

How many times has the body died? How many times has the body found its resurrection? Modern history seems to suggest that we are ill with the Frankenstein syndrome. In Shelley's tale Frankenstein is a puzzle-man, a creature made of human parts artificially assembled together to perform life. His story inaugurates the modern approach to artificial men (that is, created through science, and not by means of magical procedures). It is this desire of playing God with the flesh, that we can call the Frankenstein syndrome. ""You would have to develop an anus." [Magdescu says]

"Or the equivalent."

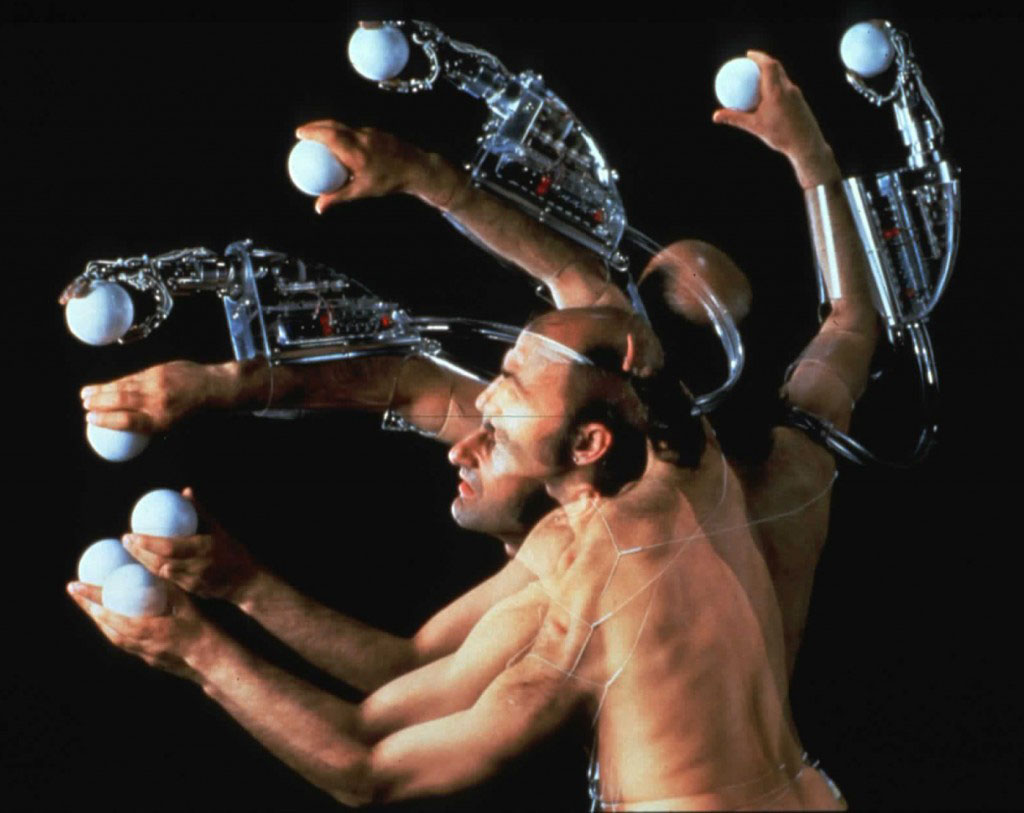

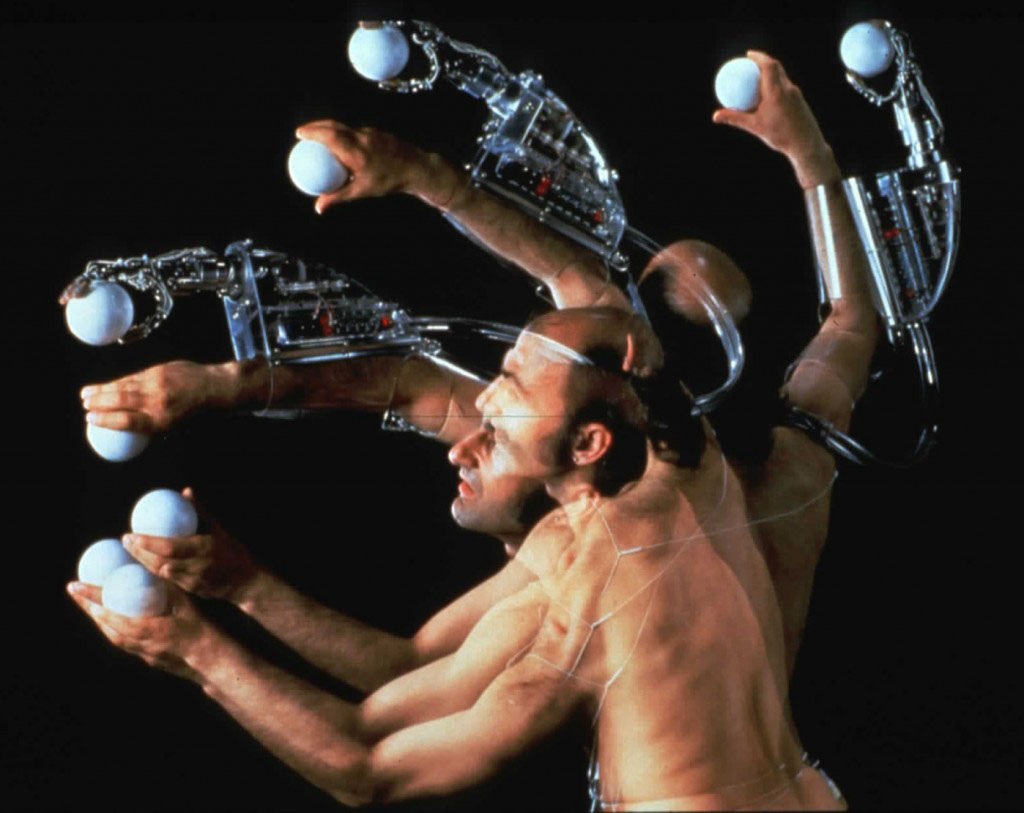

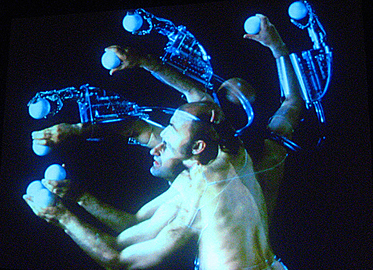

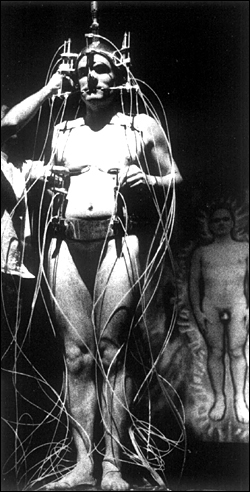

"What else, Andrew ...?" "Everything else." "Genitalia, too." "Insofar as they will fit my plans. My body is a canvas on which I intend to draw..." Magdescu waited for the sentence to be completed, and when it seemed that it would not be, he completed it himself. "A man?" "We shall see," Andrew said.(4) Andrew has already obtained freedom, but he wants more than freedom, more than a free metallic face on a free metallic body; he wants a body made of flesh, he wants an anus and genitalia. He wants to look like a man, to breathe like a man, to defecate like man. But these accessories won't make of him a man. He knows that a fundamental barrier divides his robotic essence from humanity: death. He can change forever his body, but cannot die; his positronic brain cannot meet the dissolution of the flesh.  Andrew's specular image, complement, and biological antagonist is Sterlac, an Australian performer artist of the age of dissolution of the biological body. He sees his body as a canvas, too, a canvas to be "replanned" by using technology.

He writes:

It's time to wonder if a biped body, which breathes, provided with a binocular vision and with a 1400 cc. brain is an adequate biological form. [...] The body is a structure neither very efficient, nor particularly strong. [...] The body lacks a modular project, and its ultra-reactive immunological system makes it difficult to change its malfunctioning organs. [...] The body is obsolete. [...] Technology is no longer added to the body, but it is also fixed to it. Technology is no longer the container of the body, but it becomes its component. [...] It's no longer an advantage to be "human", or to evolve as species, evolution ends when technology invades the body. When technology gives each individual the potential to progress in his own individual development, the cohesion of the species is no longer important. [...] The body must become immortal in order to adapt itself [to the new futuristic environments.] The utopian dreams will become post-evolutive imperatives. It is not a mere Faustian operation; we should not have any Frankenstein-like fear in manipulating our bodies.(5)

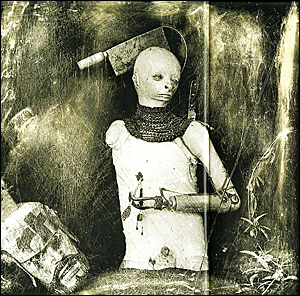

Contrarily to what happens to Andrew, Sterlac seems to be affected by what we can call the Olimpia disease. In Hoffmann's tale "Der Sandmann" ("The Sand-man"(6)) Olimpia is Frankenstein's mechanical counterpart, and the prototype of all the robots to come in the age of technical reproduction. She is a creature made of pieces assembled together, too. But she is just a collage of wheels, gears, tubes, pistons, levers, wires and iron parts, and her beauty, her exquisite human features, are only simulations of humanity. In a sense, Sterlac's dream is to become Olimpia's mechanic grandchild. The goal of his delirious, fascinating project is to create a cyber-body, a human-machine hybrid system, "an extended system, able not only to sustain the Self, but also to emphasize its operativity and intelligence."(7) The multiple body

In different ways, Sterlac and Andrew mark two symbolic extremities in a territory describing the ontological (and inevitable) faltering of the concept of body. This territory opens up the way to a double motion: from the being-of-flesh to the being-of-metal-and-plastic-and-electronics, and back again to the being-of-flesh. During this motion, Frankenstein's figure vibrates in our unconscious. We are at once fascinated and frightened by him; he's like a deformed brother of us, close enough to us to be called a man, yet too much of a monster to be considered human. He lives in a middle-land between ours and Olimpia's. He is almost like us, but he cannot be us. Or, at least, this is what we like to think. We want to believe that he lives his unnatural life at a distance from us.

While crying against the amputated foot stitched to the amputated leg stitched to Frankenstein's body, we wear and use with ease prosthetized devices, artificial limbs, and organs to reshape, according to our new needs and desires and habitats, the inside and the surface of our bodies. We have developed the art of the body and the philosophy of the body and the technology for (of) the body. And we have internalized the attributes and apparatuses we have inserted in and on our bodies, so that we no longer feel them as extensions and intrusions, as something other from us, distant from our skin, from our flesh, from our organs. We've learned to see them at work on us and believe in them, and we feel them as parts of us, as us. What Frankenstein would say if he could take a good look at our natural bodies, if he would want to try to give them a shape, a definition?(8) We know that each (ap)perceptive act is a social (and linguistic) act; by perceiving any sort of 'object' (and, therefore, by identifying it, categorizing it and recognizing it according to some cultural conventions) we (re)create it. Could the body, our natural body, escape from this constant process of redefinition and reconstruction?  Certainly we need to avoid the unconditional acceptance of the Utopia of the New Electronic World. The technological body is a new object still to be explored and understood. A powerful object. A potentially dangerous object that could take us on the verge of a virtual totalitarianism(10). So not only do we need to understand its new identity as a technological object, but we also need to carefully understand how this object functions and will function within the social contexts, and how it will affect the social games of power.(11) But this does not automatically means that we have to get rid of it. Isn't there a way of dealing with the new electronic Frankenstein so that the discourse on the virtual body can be carried out both without the blind faith for a technological heaven, and without the fear of sinking into oblivion, into a land with no more substance and meaning?(12)

NOTES Mary, Shelley. Sterlac. (1) . Paul Virilio. "Du corps profane au corps profané." Art Press Spécial n.12, 1991: 123. (The translation is mine.) (2) . Roberta, Aita. "Dalla carne al virtuale. Intervista ad Arthur Kroker." Virtual. Mensile di Realtà Virtuale e Immagini di Sintesi September 1994: 30. The translation is mine. (3) . Of course, I am aware of the fact that I am somehow banalizing Virilio's and Kroker's positions, reducing their arguments to a sort of black-and-white set of statements. But, independently from the correctness of my analysis of their positions, they help me to present the gist of an emerging negative attitude (I would say, quite often based on the common-sense belief that the old, safe world is always better that the new, unknown one) towards the electronic age. (4) . Isaac, Asimov. "The Bicentennial Man." Fiction 100. An Anthology of Short Stories. Ed. J.H. Pickering, New York: Random House Inc., 19765, p.59. (5) . Sterlac. "Prosthetics, Robotics, and Remote Existence: Post-Evolutionary Strategies." Second International Symposium on Electronic Arts (SISEA). Proceedings. Ed. Wim van der Plans, Groningen: SISEA, 1990, 227-236. Since I could not find the original version of this essay, I used sections from its Italian translation: "Da strategie psicologiche a cyberstrategie: prostetica, robotica ed esistenza remota." Ed. Pier Luigi, Capucci, Bologna: Baskerville, 1994: 61-76. Therefore, the re-translation into English is mine. (6) . Ernst T.W., Hoffmann. "The Sand-man". Weird Tales. Trans. J. T. Bealby. New York: Books for Libraries Press, 1970, 168-215. (7) . Sterlac. "Prosthetics, Robotics...", cit.: 73. (8) . Lazy writer of papers, with no room for more articulated words, I let a list speak for me, and tell about some categories used for the definition of the body. Taken out from the library computer, far from being exhaustive, this list shows nevertheless a variety of cultural tools usable for possible identifications of the 'natural' body. Here is the list: body and mind; body and soul in literature; body and soul in philosophy; body and soul in theology; body art; body building; body care; body centered psychotherapy; body composition; body fluids; body heat; body height; human body in folklore, in composition, in computer simulation, in congress, in dictionaries, in growth, in juvenile films, in literature, in legislation; human body subjected to radiations; magnetic fields of the body; moral, ethical, mythological, poetical, psychological, religious, symbolic, and social body; and... (9) . A concept, this, that, independently from its theoretical formulation, seems to me very difficult to concretely realize, even in the questionable case in which we would really want to get rid of our physical body. (10) . Cf. Roberta, Aita. "Dalla carne al virtuale. Cit.: 29. (11) . In particular, I think that an interesting study on the technological body could be carried out by using an approach similar to the one Foucault used when dealing with the concept of author in his "What Is an Author?" Rethinking Popular Culture. Contemporary Perspectives in Cultural Studies. Ed. Chandra Mukerji and Michael Schudson, Berkeley-Los Angeles-Oxford: University of California Press, 1991. 446-464. The question: "What is the technological body?" should then be immediately followed by the other question: "How does the technological body function within the social practice?" On this see also D. Haraway. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women. The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991. (12) . Cf. Paul, Virilio. "Du corps profane...", cit.: 124.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Roberta, Aita. Isaac, Asimov. Jean, Baudrillard. Pier Luigi, Capucci (ed.). Michel, Foucault. Renato, Giovannoli. Donna, Haraway. Ernst T.W., Hoffmann. Paul, Virilio. |

Leave a Reply