non-fiction

Augmented Total Theatre: Shaping the Future of Immersive Augmented Reality Representations

FotoScambio

Protected: Augmented Learning – The development of a learning environment in augmented reality

Gli ipertesti e la comunicazione multimediale

Analysis Of An E-Learning Augmented Environment: A Semiotic Approach To Augmented Reality Applications

Augmented Learning: An E-Learning Environment In Augmented Reality For Older Adults

Narrativa ipertestuale? Non ancora, grazie!

Le strutture della narrativa ipertestuale

fiction

Is there a mind in this mind?

| University of Florida - 1995 |

|

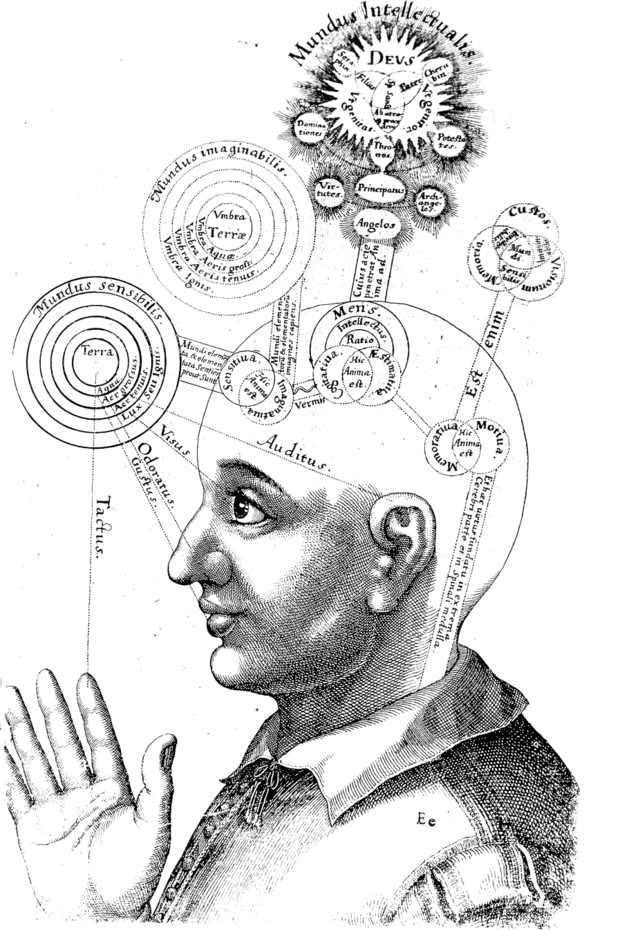

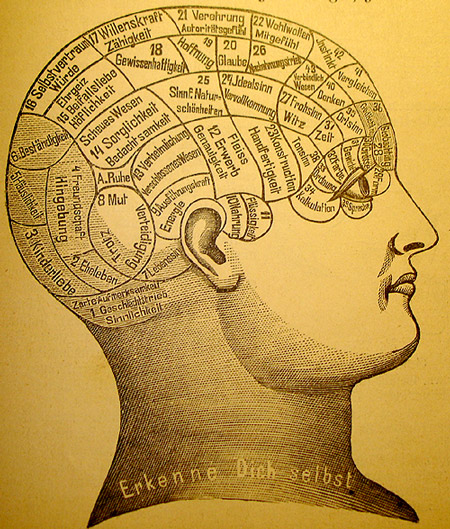

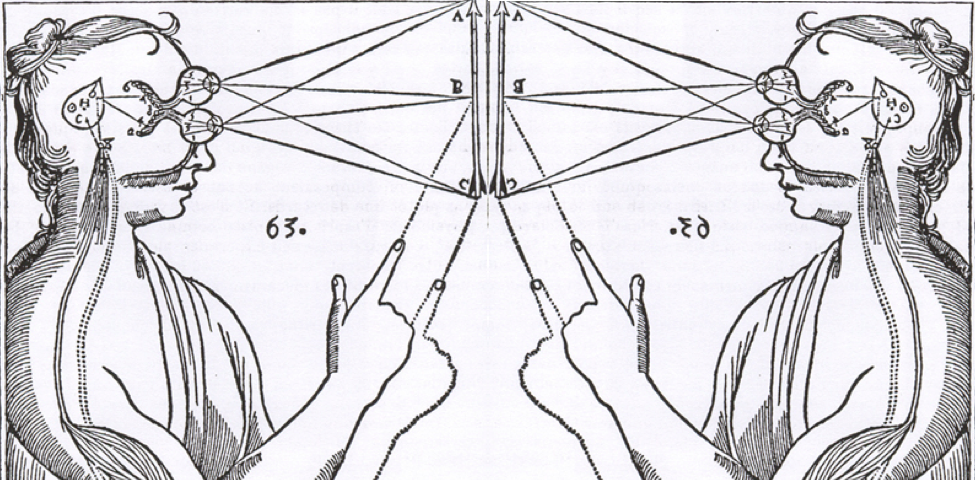

After the exploration of the dissolution of the concept of body, it is time now to move on to the investigation of what the body is not, or what it seems not to be. The body, we have seen this, is a cultural and linguistic object, sick with an illness that is a mixture of the Frankenstein syndrome and Olimpia's disease. We, bio-mechanical mutants of the Western World, have found thousands of ways to define properties and malleability of our natural bodies: biological bodies, dismembered bodies, cybernetic bodies, electronic bodies. But some questions seem to inevitably buzz around this multitude of bodies: what is the limit of bodily metamorphosis? Is there in us a hard nucleus, untouched by and untouchable during all the transformations our body is going through? In other words: if we change, piece after piece, our physical substance, when does the last change trigger the fly of our soul, so that we become just an assemblage of bio-mechanical devises deprived of humanity? A micro-history of the mind

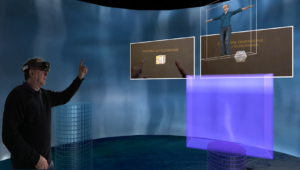

Of course, the above questions are far from being new. Moreover, they cannot avoid resembling the ones already formulated for the birth and the growth of the concept of body. After all, what are we made of, but of body and soul? Many have been the answers to these questions. From Thales of Miletus to Wittgenstein there is a short jump, few millennia represented by a list of names and ideas: Plato, Aristotle, Berkeley, Hobbes, Descartes, Spinoza, Hume, Fichte, Kant, Hegel, Freud, just to mention a few of the many thinkers involved in the task of capturing the essence of the nous, the mind, or the soul; materialism, idealism, dualism, and their multiple ramifications, have been the wise contributions of those thinkers to the creation of the mind as a multi-faced concept. Yet, through the centuries there hasn't been much really new on the problem. After all, it was not that easy to be completely sure about the absolute materiality of the mind when an open skull showed only the trembling of grey matter; were the thoughts really hidden in that wet mass? Nor was it so easy to hold certainties about the soul as a projection of God's mind, since God was sometimes even more uncapturable than the soul itself. In any case, millennia of history of exploration of the soul-mind can be described as the verbal traces left by the unstable vibrations of the thought around two broad, contradictory principles: (a) the mind is matter; (b) the mind is not matter.  More recently, after a 'natural' drying up of the pineal gland, and after a difficult and long burial of the classical dualism, a good, positive, and pragmatic attitude, and the growth of scientific knowledge have took over the debate on the soul from the shaky hands of philosophers, and have made of the newborn mind the sophisticated object a new science: the science of mind, the cognitive science. (1) Yet, the actual questions asked in that scientific domain are not really different from the ones Plato's Socrates asked his doubtful and curious disciples: what is the mind? Where is it? How does it work? Moreover, not even the sharp eye of science seems to be able to easily capture the mind, and things do not look that clear and solved as they should in a world controlled by models and formulas and objectivity. Apart from the ideas still carved in the minds of a few philosophers still busy with the search for mysterious connections between the body, the soul and God, one thing seems to be commonly accepted: the definition of mind is a matter of matter. The mind is some sort of physical interface between the body and the environment; the mind is that tangible part of our body that --unique in its kind -- allows self-definition, self-construction, and self-analysis. Vague enough to be undeniable, this is the common ground, the starting point for the contemporary discourse on the mind. But from that point on, the concept of tangibility becomes rather intangible, so that many different theories on the mind have been developed and have found different and conflicting paths. With no room for details, here generalization (with its dangerous consequences) is a must. Then, assuming materialism in the background, through the eye of generalization, we can identify two new guidelines for the contemporary search of the mind: (a) given the uselessness of the mind in the discourse on mind, the mind should be killed, or identified with the brain; (b) given the importance and irreducibility of the mind, the mind should be given an almost-but-not-completely-physical-although-not-metaphysical status. In one way or another, the theories suggesting the killing of the mind, such as Behaviorism or the Central-State theory, have tried to forget about the existence of mental states. To identify the mind with observable behavior is a nice move, but what about the inner behaviors, the ones activated by external percepta and producing (through inner actions, behaviors) chains of internal changes producing, in turn, some kind of external, observable behavior? (2)  This could be enough to show the unwillingness of the mind to be captured. But it is not, and in very recent years things got even more complicated. Computer simulations, parallel distributed models, expert systems, almost-functioning iso-functional models, artificial intelligences (5) are becoming the mental prostheses of our "natural" mind, in addition to the prosthetized apparatuses we incorporated (with)in our natural body. They reshape the environment in which we live, of course, and we learn new ways to adapt ourselves to the newly created environment. But are we so sure that we can trace a clear-cut line between us, mind-bodied beings, and what is around us? Brain-less bodies, body-less minds and satellite skins

At this point, after so many confusing questions, a question rises in my mind: what kind of definition of mind should I trust? In what kind of mind should I entrust my soul? Again, there is not much room left here for discussion and articulation. So, the answer I can find --if I feel so dare to talk about answers without smelling the hot breath of the cultural-studies-creature on my neck -- is, as the old, good Aristotle once said, in the middle ground. Or rather, as I (more modestly, and in less need for foundations) would put it, in the unsteady land of multiple, co-existing definitions.By paraphrasing and (or) echoing the (maybe too) many words read and listened during my first landing in the Cultural Studies Planet, I could only come to the following, inconclusive conclusion: a new set of questions.  My previous investigation on the body laid down some basic questions: what is going to happen to our body, more and more extensively manipulated by language and technology? Will it vanish, or sink in the ocean of nihilism, as it has been foretold by the theoreticians of purity and naturality? Or will it rather find its new substance and new properties, its "satellite skin," (6) in the landscape of the hyper-technologized Twenty-First century? This superficial investigation on the mind cannot avoid similar questions, once mostly found in science-fiction stories with an itch for philosophical adventures: what is this mind, so much looked for, and never really grasped? How many minds can we find in our mind? Do we still need to live with the poly-centennial and by now canonical split between body and mind, between a physical, inert substance and an intangible matter in charge of supervising the behavior of that substance? Do we still need to talk of the existence of a core that defines our real reality? Will we really be able to create a model of mind completely iso-functional with our own? Will we really be able to reach immortality by getting rid of our body, and by transplanting our mind in a less damageable and replaceable bio-mechanical support? Will we really be able to make copies of our minds and spread them over the world, as we do now with multimedia files? Will we really be able to travel to other planets by transferring one of these copies into a far-away body-host? Are we going to evolve, according to a mysterious and magic and metaphysical and teleological Great Plan, into mind-particles in a electronic mind-network wrapped around the world? (7) If the body is replaceable with bio-mechanical devices, if the mind is transferable on external non-biological supports, and is multi-copiable through electronic devices, and spreadable over the whole world, what is left of us, for us, in us? For our poor natural body and our small real mind? Sit on a rock, thoughtful, Ibsen's Peer Gynt thinks of himself as a copy of the onion he holds in his hands. He is a layered onion-like being constructed with and through the experiences of his life. Shouldn't we mirror ourselves into that thoughtful Peer Gynt? Shouldn't we try to picture ourselves as multi-layered beings with no core, but as huge, interactive, evolving physical-biological-linguistic-symbolic-electronic onions, with layers to peel off or to add according to our changing theories, languages, needs, desires, passions?

NOTES (1). For a history of the new science of mind see Howard, Garner. The Mind's New Science. A History of the Cognitive Revolution. New York: Basic Books, Inc., Publisher, (1985) 1987. See also Francisco, Varela. The Science and Technology of Cognition. Emergent Directions, 1986; Sergio, Cicconi. Il funzionalismo nella filosofia della mente. Unpublished dissertation, University of Padua, 1988. (2). For an account of Behaviorism and its problems see Broadbent. Behavior. London: Eyre Methuen Limited, 1960; Curi. Il problema dell'unità del sapere nel comportamentismo. Padova: CEDAM, 1967; Fodor. "The Mind-Body Problem." Scientific American, n.14 (1981):124-132;Moravia. L'enigma della mente. Bari: Laterza, 1986; Cicconi. Il funzionalismo nella filosofia..., cit.. (3). For an account of the Central-State theory and its problems see Fodor. The Language of thoughts. Cambridge: Harvard University Press: 1975; Churchland. Scientific Realism and the Plasticity of Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979; Block & Fodor. "What Psychological States Are Not." Reading in Philosophy of Psychology, I. Block, N. (ed.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980: 237-249; Fodor. "The Mind-Body Problem." cit.; Gardner. The Mind's New Science. Cit.; Moravia. L'enigma della mente. Cit.. (4). This term is used by V.A. Venikov in Theory of Similarity and Simulation. London: MacDonald, 1969. It should be noted, though, that the concept of mind as functional system had already been developed by several other researchers before Venikov. See, for example, all the work done by Fodor and Putnam, the promoters of that particular materialistic-dualistic approach to the mind that has been called Functionalism. Here I give only the titles of a few of the many texts they have written on the subject. Fodor. The Language of thoughts. Cit.; Fodor. "The Mind-Body Problem. Cit.; Putnam. "Minds and Machines." Dimension of Mind. Hook, S. (ed.). New York: New York University Press, 1960: 148-179; Putnam. "Philosophy and Our Mental Life." Mind, Language and Reality. Philosophical Papers. London: Cambridge University Press, 1975. For a critique of Functionalism three important texts are: Kalke. "What is Wrong with Fodor and Putnam's Functionalism." NOUS, n. 3 (1969):83-93; Block. "Troubles with Functionalism." Perception and Cognition. Issues on the Foundation of Psychology. Savage, W. S.(ed.). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1978: 261-325. Block & Fodor. "What Psychological States Are Not."Cit.; For a more contemporary functional approach to the mind see Dennet. Brainstorm. Philosophical essays on Mind and Psychology. Montgomery: Bradford Books, (1978) 1986. (5). Just to point out a few names, cf., for example, Rumelhart & McClelland. Parallel Distributed Processing, I-II. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1986; Dennet. Brainstorm... Cit... For an overview of Artificial Intelligence see the new edition of Winston. Artificial Intelligence. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, (1984) ?. See also and all the work done by M. Minsky at the MIT. (6). "Satellite skin" is the word used by Maldonado to describe the almost limitless extendibility of the contemporary technological body. See Maldonado. "Corpo, tecnologia e scienza." Il corpo tecnologico. Cit.:77-97. (7). These very contemporary themes had already been developed in the past by science-fiction writers such as Sheckeley (Mindswap, The Alchemic Marriage of Alistair Crompton),Asimov (with all the stories with his positronic robots), Heinlein (I Will Fear No Evil), and, more recently, Gibson, with his famous Neuromance, orHarrison and Minsky (the father of A.I.) with their Turing Option, but also, in a less scientific context, by writers such as Bulgakov with his Dog's Heart, or Stevenson with Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. To explore these ideas within a more theoretical framework see, for example, Giovannoli, R. La scienza della fantascienza. Bologna: Bompiani, 1991; Haraway. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women. The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991; Laiteiner. Of Man, Mind and Machine: Meme-Based Models of Mind and the Possibility for Consciousness in Alternate Media, 1992. Found in Internet in the gopher of Principia Cybernetica Web. Joslyn, C., Turchin.. Cybernetic Immortality, Aug. 1993. Found in Internet in the gopher of Principia Cybernetica Web; Capucci (ed.). Il corpo tecnologico. L'influenza delle tecnologie sul corpo e sulle sue facoltà. Bologna: Baskerville, 1994.

BIBLIOGRAPHY Block, N. Block, N., Fodor, J. Broadbent, D. E. Capucci, P. L. (ed.) Cicconi, S. Churchland, P. Curi, U. Dennet, D. Fodor J. A. Gardner, H. Gibson, W. Giovannoli, R. Haraway, D. J. Harrison, H., Minsky, M. Ibsen, H. Joslyn, C., Turchin, V. Kalke, W. Laiteiner, J. S. Maldonado, T. Moravia, S. Putnam, H. Rumelhart, D., McClelland L. Varela, F. Venikov, V. A. Winston, P. |

Leave a Reply